1) For most of the papacy’s history, popes were elected by the clergy and people of Rome through some form of acclamation. Over time, the role of the laity and the non-cardinal clergy was gradually reduced, but the possibility of the cardinals electing a pontiff through acclamation was not removed until 1996. To this day, the people’s acclamation of the new pope continues in some form when the new pope presents himself to the crowds in St. Peter’s Square.

2) The cardinals did not become the principal electors of the pope until 1059, but even then the laity and clergy of Rome retained the right of confirmation.

3) It was not until 1179, at the Third Lateran Council that a formal voting procedure for the cardinals was put in place, requiring a two-thirds majority.

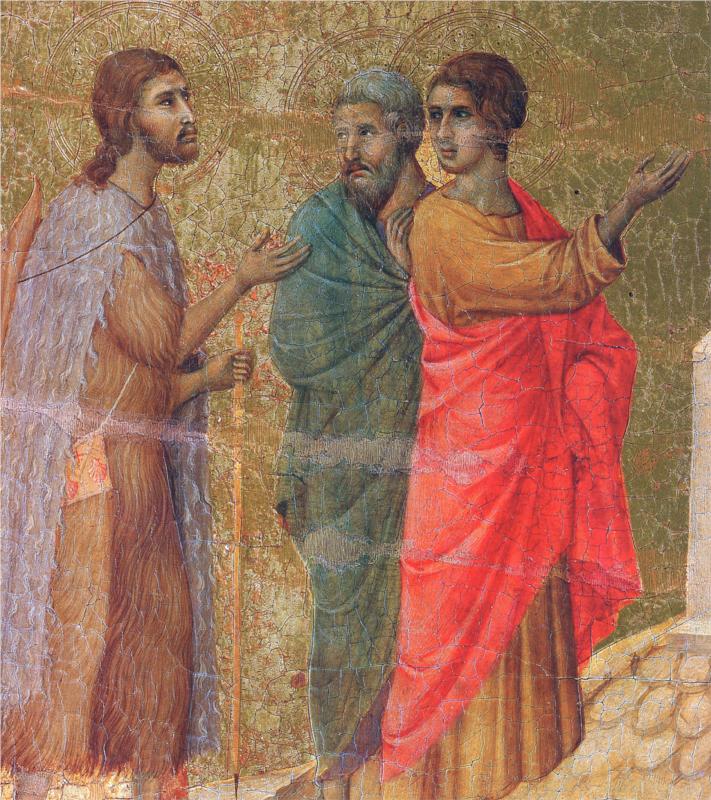

4) The first conclave happened in 1271. It was a spontaneous event that occurred against the will of the cardinals. The papacy had been vacant for nearly three years and the people of Viterbo, where the 12 cardinals were gathered, had had enough. They locked the cardinals in the church and forbid them access to the outside world. Finally, the townspeople started restricting the food that entered the church and even took the roof off to expose the cardinals to the elements. Finally, they elected Blessed Gregory X pope. At the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, Gregory promulgated a decree that mandated a conclave for papal elections, modeled directly on what the people of Viterbo had done—it included the provision that after three days the cardinals were to be given only bread and water.

5) The cardinals can elect any baptized man pope. Pope Gregory X was not even a priest when he was elected in 1271. In a matter of days he was ordained through the minor orders and the priesthood, and was consecrated bishop. He was then made bishop of Rome and pope. Pope Urban VI (1378–1389) was the last pope who was not a cardinal before election. Nevertheless, John Paul II’s 1997 apostolic constitution on papal elections lays out the procedure to be followed if the cardinals elect someone outside the college as well as someone who is not yet a bishop.

6) In the papal election of 1417, which definitively ended the Western Schism, the conclave included 30 non-cardinal delegates representing the “nations”: France, Germany, Italy, England, and Spain.

7) There will be 115 cardinal electors in this conclave. Historically, this is a huge number. Indeed, in the conclave of 1261, there were only seven cardinals.

8) The first conclave held in the Sistine Chapel was that of 1492. This was 16 years before Michelangelo began working on the chapel’s remarkable frescos. In 1492, it had bare walls and ceiling.

9) Popes have not always changed their names when elected. John II in 533 seems to have been the first to do so, but for the first thousand years of the Church’s history, it was very rare. After 996, almost every pope chose to change his name to that of a previous pope, but not all. Marcellus II, who was elected in 1555, was the last pope who kept his baptismal name. While Pope John Paul I changed his name at his election in 1978, “John Paul” was the first new papal name in over one thousand years.

10) The Roman emperor had a significant role in the election of popes for the majority of the papacy’s history. This role was normally limited to confirmation of the candidate. Until the eighth century, new popes sent to Constantinople for their election to be confirmed by the emperor of Byzantium. After Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne “Roman Emperor” in the year 800, the right of confirmation shifted to the Franks and what would become the Holy Roman Empire. The involvement of secular governments in papal elections went through many changes, culminating in the so-called “right of exclusion” through which the cardinal representatives of France, Austria, and Spain could “veto” a papal candidate. This was last exercised by Austria in 1903, and Pope Pius X definitively abolished this “right” in 1904, laying down excommunication for any cardinal who might try to evoke it in a conclave.

[…] via Ten Things You Might Not Know about the History of the Conclave « Scripture Study Software. […]

[…] Ten Things You Might Not Know about the History of the Conclave « Scripture Study Software. […]

[…] Here are Ten things you may not know about the conclave […]

The Sistine Chapel’s ceiling and walls were not bare in 1492 – the ceiling had an ancient fresco of Our Lady and stars on a blue field and the walls also had frescos.