Last year, Andrew wrote a fantastic piece about how the meaning of Mardi Gras has dramatically changed. Andrew dismissed the idea that medieval Carnival was simply a “pressure valve” to release social tension, or a carrying-over of the “folk culture” against the repressive culture of the upper classes. Instead, it’s more helpful to understand that the medieval person lived with a different sense of time:

To the medieval mind there were really two courses of time. There was the linear time of sequence—one thing came after the next, forever—and there was the higher-order time through which the transcendent came into contact with the immanent . . . Before the reign of Grace, there had been a time of the reign of the body . . . it was a time of moral and social chaos . . . Carnival was a participation in this part of the drama of redemption. [read more]

Today I want to elaborate on this idea and show not only that Carnival was an explicitly theological event, but that it even has biblical precedent.

In 2 Samuel 6:14, King David does something very similar to the carnival actors in the Middle Ages. He “plays the fool,” dancing nearly unclothed in the streets with reckless abandon:

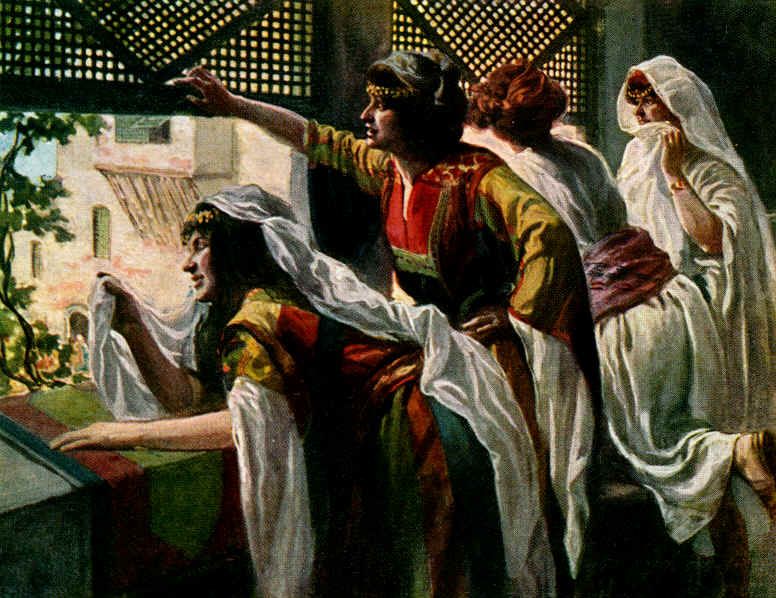

Wearing a linen ephod, David was dancing before the LORD with all his might, while he and all Israel were bringing up the ark of the LORD with shouts and the sound of trumpets. As the ark of the LORD was entering the City of David, Michal daughter of Saul watched from a window. And when she saw King David leaping and dancing before the LORD, she despised him in her heart . . . . When David returned home to bless his household, Michal daughter of Saul came out to meet him and said, “How the king of Israel has distinguished himself today, going around half-naked in full view of the slave girls of his servants as any vulgar fellow would!” David said to Michal “It was before the LORD, who chose me rather than your father or anyone from his house when he appointed me ruler over the LORD’s people Israel—I will celebrate before the LORD. I will become even more undignified than this, and I will be humiliated in my own eyes. But by these slave girls you spoke of, I will be held in honor.”

Wearing a linen ephod, David was dancing before the LORD with all his might, while he and all Israel were bringing up the ark of the LORD with shouts and the sound of trumpets. As the ark of the LORD was entering the City of David, Michal daughter of Saul watched from a window. And when she saw King David leaping and dancing before the LORD, she despised him in her heart . . . . When David returned home to bless his household, Michal daughter of Saul came out to meet him and said, “How the king of Israel has distinguished himself today, going around half-naked in full view of the slave girls of his servants as any vulgar fellow would!” David said to Michal “It was before the LORD, who chose me rather than your father or anyone from his house when he appointed me ruler over the LORD’s people Israel—I will celebrate before the LORD. I will become even more undignified than this, and I will be humiliated in my own eyes. But by these slave girls you spoke of, I will be held in honor.”

There are two things I want to point out here:

1) David, in the face of the “moral criticism” coming from Michal, defends his actions by saying that he did them “before the LORD.” David didn’t act for the sake of carnal indulgence or merriment—his antics had a fundamentally theological meaning and purpose.

2) David mentions that he will be “humiliated” in his own eyes. What is happening here except for a kind of role reversal? Just as paupers and layfolk would, in medieval Carnivals, play priests and bishops (reversing their social and ecclesial roles), so too David acted like a “fool,” abandoning, temporarily, his dignified position as king.

These two elements—his reckless abandon before the LORD and his “self humiliation” are both elements we can see in the medieval Carnival. But it’s important to remember that these actions always exist within the larger season of Lent—a season of repentance and one of the few (if not only) times a person would participate in the Sacrament of Confession every year. Carnival was part of a drama, connected to the meaning of sin and redemption, fundamentally linked to the worship of God.

Though the scene of David’s dancing in 2 Samuel isn’t a Carnival per se, it does show that there is biblical precedent for the kinds of ecstatic action that we see in Christian celebrations like Carnival in the Middle Ages. It’s hard for us to understand the role that something like Carnival plays in a modern age that’s moved so far from a sacramental worldview. But we can see that, in the context of a world in which time is marked by seasons within a liturgical framework, the actions of individuals and communities take on different meaning.

The question we face in the midst of suffering or celebration doesn’t terminate in whether or not our experience was “good” or “bad”—but rather what meaning our experience has. As Andrew mentioned last year, the debauchery of Carnival in the Middle Ages certainly wasn’t “morally good” behavior—but then again, King David’s half-nude dancing wasn’t exactly morally exemplary. But this is the whole point—our behavior takes on a different meaning in the context in which it was enacted. Does this mean that all of the behavior in a medieval Carnival was good? Of course not. But to ignore the liturgical context in which these events transpired is to miss the heart of both Carnival and Lent.

Can Carnival today mean what it meant in the Middle Ages? Most likely not—we live in a culture broken away from a Christian sacramental view of the world: our shared conception of time is not liturgical. Because of this, Mardis Gras tends to end up being revelry for revelry’s sake, with no understanding of the great drama of sin and redemption that surrounds all our social acting. I don’t think this means we can’t enjoy ourselves on Tuesday night, however. In fact, just the opposite—if we think carefully about Mardis Gras’ historical meaning, then—as we celebrate, like King David, “before the LORD”—our celebration becomes truly meaningful.

As we go forth into a season of fasting and repentance, let us remember that the same principle applies to our suffering as well as our celebration. We celebrate with reckless abandon, and sacrifice our whole lives—not for ourselves or before our fellow men, but before God.

“Commit your work to the Lord, and your plans will be established” (Prov. 16:3).

Join us as we study the Gospel this Lent

If you haven’t already, sign up for free daily gospel reflections delivered right to your inbox. Journey alongside others as you share your thoughts and reflections in the Verbum Lenten Journey.