By Eva Marie Haine

In April, I explained some basic principles of how to look at art from a purely formal point of view—that is, an analysis of how an object of art looks in terms of elements of design. These elements are line, shape, form, color, value, texture, and space.

Any good appreciation of a work of art begins and constantly returns to its form. Why? Because how it looks is inseparable from what it shows or expresses —the visual is the conduit of expression which makes art distinctive from every other form of expression. Thus art cannot be reduced to its subject matter, historical background, or facts of an artist’s biography, which might aid in our understanding of the work, but will never amount to its whole meaning, and in fact, are many times a distraction from it.

Art is not a historical record, nor is it mere imitation and representation. Indeed, realism in art can make art a slave to the literal. Instead, art is a way in which the human act of making distills and soaks the visual world with ideas, feelings, and spiritual realities. These are things that words cannot express adequately and reason cannot grasp. Our intellect delights in the masterful marriage of form and content. In his Beauty: A Very Short Introduction, the philosopher Roger Scruton describes how good art appeals to the imagination and comes to us “soaked in thought.”

The truth is that it is perfectly good and even right to feel a sense of wonder and mystery about a work of art. The French Thomist Jacques Maritain writes in Art and Scholasticism, “In the presence of a beautiful work… the intellect rejoices without discourse […] It is thus that it signifies without properly making known, and that it expresses that which our ideas cannot signify.” To experience speechlessness is indeed the telling effect of great art.

Sadly, many times we do not allow ourselves to linger in that space of wordless wonder, but immediately want to resolve our questions by appealing to information. It is easy, especially in our hyper-informed age, to jump immediately from looking at a work of art to explaining it. If you go to a museum and observe visitors there, you will see that most of them glance briefly at a work of art, read the text alongside it, and then walk on. Sometimes they don’t even look at it, they just take a picture of it! The internet-surfing equivalent is to see an image of art and immediately read about it on Wikipedia.

For this reason, I suggest in my first article that when you encounter a work of art that strikes you, do not read about it. Instead, enter into the painting by means of close analysis. Find an entrance point that interests you—perhaps the color or the composition—and then allow your eyes and your mind to wander through the painting. You will discover all sorts of distinct details that lend themselves to the overall beauty and impression that it gives you.

By doing this, you will begin to have a sense of the meaning—what the work communicates. This is true even for abstract art, which still conveys and communicates, although more vaguely than figurative art that tells a story or represents a particular scene or person.

Maritain notes that in order to have this experience, there must be something legible to us–something that we recognize and can understand what it signifies. Deeper truths sometimes require deeper knowledge, and I think that this is true of much religious art. To an observer with very little knowledge of Scripture or theology, there may be little that is legible in a painting of the Crucifixion; the full significance of the details may be lost on them. On the other hand, such a person may be more receptive to the affective power and mystery of the scene, whereas those who are very familiar with the story and with the common artistic tropes of it might be desensitized to the potency of the truth expressed.

Thus, knowledge is certainly helpful in apprehending the content of a work of art, and of the recognition of its essential truth, but we also must be careful, especially with religious art, not to reduce it to a mere code of symbols for us to interpret either rightly or wrongly. Let us try to always retain that wonder at the mystery of good artistry and the unique marriage of form and content that each work contains.

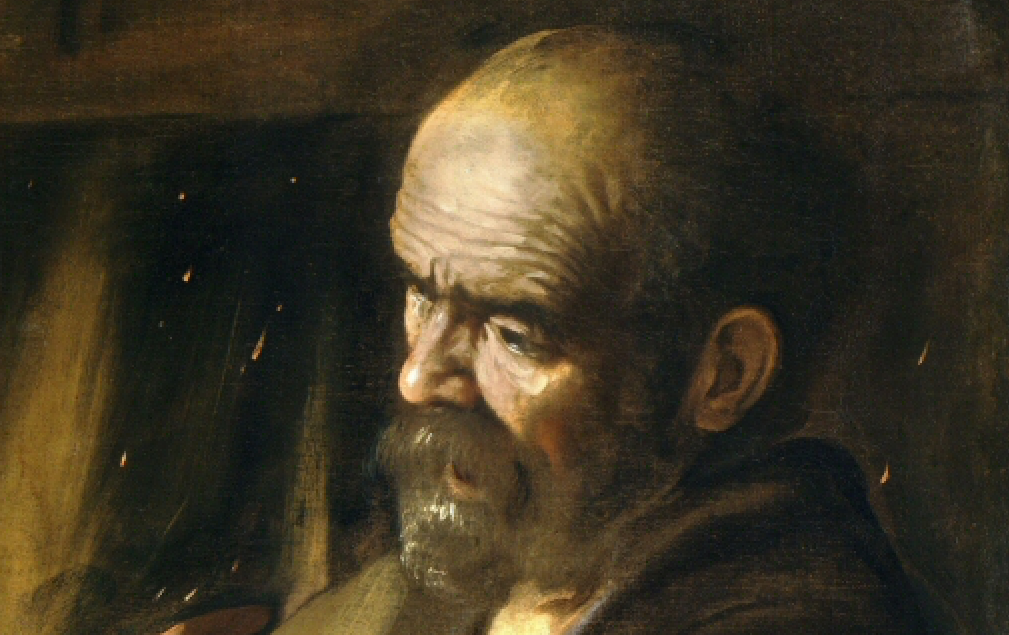

So, how exactly do we interpret those details that we see? Returning to the Descent from the Cross by Rembrandt that we analyzed in my first post, I’d like to guide us through a simple interpretation of it.

Looking back over the analysis based on our elements of design, a few key observations stand out. It seems that everything—from the color, the lighting, and composition—draws my eyes to Christ’s body and its lifelessness. Then, I can begin to ask myself what I know of this moment in Scripture: first, the dark background reminds me that there was an eclipse of the sun at the time of His death, and yet a pure light seems to be emanating from His body, piercing the darkness. Both of these aspects reveal His divinity to me, in that they make manifest His authority over and transcendence of the material, physical world. Meanwhile, His total limpness and lifelessness, accentuated by the contrast of his heavy, curving form with the straight, linear cross, and also the near-whiteness of His body, shock us with the truth of God’s death. Rembrandt is drawing out and inviting us to contemplate more deeply the mystery and scandal of this truth by depicting it with such concentrated attention. The painting holds in tension Christ’s divinity and His mortality with striking contrast.

This interpretation is what arises from my very personal and direct observation. I have not read about the painting at all. Granted, I am accustomed to looking at art, but the point of my example is not to set a standard, but to act as a guide for how to move from formal analysis to interpretation—an interpretation that is meaningful to you as a viewer. You must ask yourself: what is the painting communicating and how does it do it? Perhaps it will move you to a very simple truth, or you may find yourself following a fascinating chain of theological reflections.

If, in the end, you want to know more about the artist, the technique, the time period, and so on, feel free to read the museum placard or research it on your own. Especially in regards to religious art, the best way to lead yourself to a deeper appreciation is not necessarily to read about particular works, but to study the apposite Scripture and theology more closely. Another excellent way to grow in understanding of art is to learn how to make it yourself, if only for a greater sense of how artists use particular media and to what effects, and how they are moved to certain artistic choices for the sake of meaning. Above all, art is for delight and wonder, for understanding truths hard to express in words, so if you find yourself getting bogged down in facts, go back to looking!

All of the paintings featured on the blog are available in the Verbum Treasury of Sacred Art.