When approaching the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation, the Catholic Church teaches that we must confess our mortal sins, and that we ought to confess our venial sins, in order to reconcile ourselves with God (see CCC 1455–58). We can better avail ourselves of the healing which Christ offers through his Church if we understand what these sins are, what they are not, and how they differ.

- What distinguishes mortal and venial sins?

- What sins are considered mortal?

- What should I do if I commit a mortal sin?

- What sins are considered venial?

- What should I do if I commit a venial sin?

- Where can I learn more about sin and the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation?

Mortal and venial sins

The Church teaches that all sin is “an utterance, a deed, or a desire contrary to the eternal law” (CCC 1849). And this is true of any sin: all sin, mortal and venial, harms our ability to receive God’s love and friendship in beatitude. But it is also true that some sins are greater than others.

St. John the Evangelist explains this distinction in his first letter to the early Church:

If anyone sees his brother sinning, if the sin is not deadly, he should pray to God and he will give him life. This is only for those whose sin is not deadly. There is such a thing as deadly sin, about which I do not say that you should pray. All wrongdoing is sin, but there is sin that is not deadly. (1 John 5:16–17 NABRE)

St. John distinguishes between sin that is deadly and sin that is not deadly. The death being referred to in this passage is the death of the soul when it is separated from God’s love.

The kind of sin that separates us from God’s love is what the Church calls “mortal sin.” The other kind, “venial sin,” is sin that merely wounds our ability to receive God’s love. While the Church has fleshed out this doctrine in more detail, it is a distinction that comes to us from the earliest Apostolic teachings.

In the Catechism, the Church defines mortal sin as a sin that “destroys charity in the heart of man by a grave violation of God’s law; it turns man away from God, who is his ultimate end and his beatitude, by preferring an inferior good to him” (CCC 1855). In committing a mortal sin, we lose sanctifying grace and require the healing offered by the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation to restore that grace in our soul. Likewise, the Church teaches us that venial sin “allows charity to subsist, even though it offends and wounds it” (CCC 1856).

St. Thomas Aquinas, in his Commentary on the Sentences (II.D42.A3.Ad5), provides the following image to help us understand the difference between mortal and venial sin: Imagine you are following a map to reach a camping site where you are meeting a friend. Now, say you decide that the map is wrong and choose to turn around and go a completely different direction: If you do this, you may end up somewhere, but not where you were supposed to be going, and you won’t find your friend there. You are no longer headed in the right direction, and when you refuse to follow the map, you will inevitably fail to reach your destination. This is what mortal sin is like: We have departed from God’s directions for life, what we can call his law, and decided to do things our own way. But, by going our own way, we will not reach God.

Now imagine you are following a map to reach a campsite where you are meeting that same friend, but this time you follow the map. However, while you follow the directions and are headed to the right spot, you take a lot of stops: You sleep in a little longer before you head out; you take a detour to see the World’s Largest Ball of Twine; you stop for a burger; you get out to stretch your legs. Your friend waits at the campsite while you lallygag. This is how St. Thomas describes venial sin: You might still get where you are going, but you haven’t done it well. You might reach God, but not in a way that is actively seeking him, and if you tarry enough with enough venial sins, it becomes increasingly easier to go a contrary direction. After all, you’re already off the path, so why not try going somewhere else entirely, since it would be so much easier? This is how venial sins move us towards mortal sin.

What is a mortal sin?

For a sin to be considered mortal, there are three conditions that must be met (CCC 1857).

1. The object of the sin must be grave matter.

The Catechism explains that grave matter is a serious offense against God’s law, and these sins are given in general outline by the Ten Commandments.

First there are commandments about sinning against God: You are to have no other gods before God (Gen 20:3); you are not to take the name of the LORD your God in vain (Gen 20:7); you are to remember the LORD’s day and keep it holy (Gen 20:8).

Examples of such actions constituting grave matter include:

- Participating in horoscopes, astrology, or “or other practices falsely supposed to ‘unveil’ the future” (CCC 2116).

- Confessing atheism which “rejects or denies the existence of God” (CCC 2125).

- Making a false oath which “calls on God to be witness to a lie” (CCC 2152)

- Failing to participate in the Mass on Sundays and other holy days of obligation (CCC 2180)

Then there are commandments about sinning against your neighbor: Honor your mother and your father (Gen 20:12); do not kill (Gen 20:13); do not commit adultery (Gen 20:14); do not steal (Gen 20:15); do not bear false witness against your neighbor (Gen 20:16); do not covet your neighbor’s spouse or your neighbor’s goods (Gen 20:17).

Examples of such actions constituting grave matter include:

- Failing to give elderly or ill parents material and moral support (CCC 2218)

- Disobeying just laws (CCC 2238)

- Direct and intentional killing of another person, including abortion and euthanasia (CCC 2270, 2277)

- Viewing, participating in, or creating pornography (CCC 2354)

- Using artificial birth control or sterilization procedures (CCC 2366)

- Paying workers an unjust wage (CCC 2428)

- Committing detraction or calumny (CCC 2477)

- Looking at another with lust of the heart (CCC 2514)

- Using unjust means to acquire wealth (i.e., monopolies) (CCC 2537)

- Wishing evil would befall another for your own economic benefit (CCC 2537)

Even among grave matter, some actions are worse than others: Killing your friend is worse than lying to your friend; killing your child is worse than killing a stranger; lying to your friend on a contract is worse than lying to your friend about seeing a concert. So the gravity of the sins can vary due to many factors, such as who is wronged and the way in which they are wronged (CCC 1858).

One of the reasons it is so important to name sins like this is, as Jana Bennett and David Cloutier write in Naming Our Sins, that “naming sin is meant to be empowering—empowering in that we take real responsibility for the past and we can participate in the process of doing better in the future.”1

2. The sin must be committed with full knowledge.

For a sin to be mortal, you must have knowledge that the action is a sin and as such is opposed to God’s law (CCC 1859). So if a three-year-old child takes money from a wallet they see at a restaurant, the child has not committed a sin if they did not understand the action to be stealing and against God’s law.

3. The sin must be committed with complete consent.

For a sin to be mortal, the Catechism explains that you must have “consent sufficiently deliberate to be a personal choice” (CCC 1859). So if your spouse sterilized himself or herself against your expressed wishes, you would not be culpable because you did not consent to the sin of sterilization. However, the Catechism reminds us that “feigned ignorance and hardness of heart do not diminish, but rather increase, the voluntary character of a sin” (CCC 1859). So if you pretend to not know that a wage is unjust, or if you use hollow reasons to pretend it is just when you are well aware that it is not, then you might be more culpable of defrauding a worker of her wages, not less culpable.

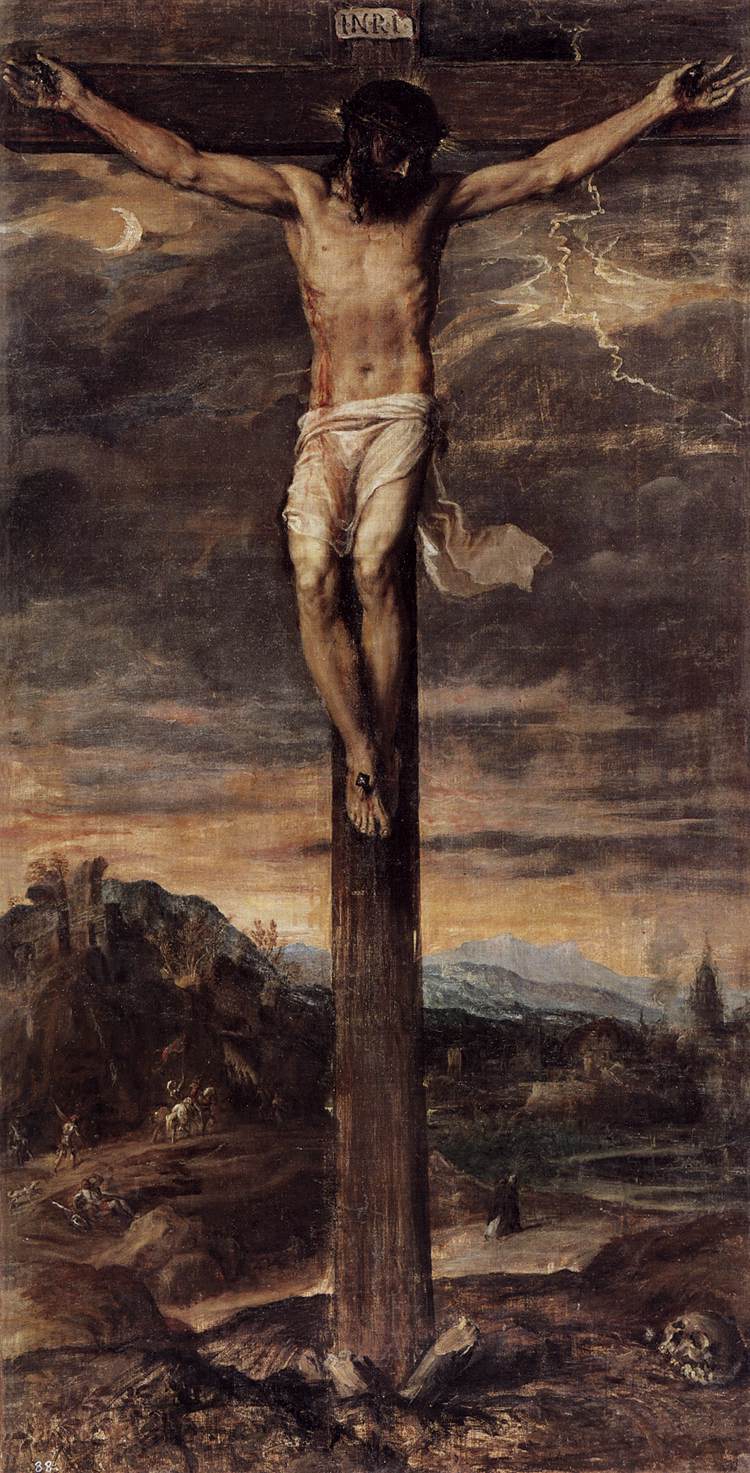

What if you have committed a mortal sin?

If you have committed a mortal sin, you have lost sanctifying grace. You have ruptured communion with God and the Church (CCC 1440). If you are in this state, you must receive God’s forgiveness and be reconciled with the Church. Until you do so, you are obliged to avoid receiving the Eucharist.

This reconciliation with God and the Church occurs through the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation. The Catechism teaches us that “Penance requires … the sinner to endure all things willingly, be contrite of heart, confess with the lips, and practice complete humility and fruitful satisfaction” (CCC 1450).

Contrition of heart, as St. Francis de Sales wrote, requires that you “not only cease to sin but you must also purify your heart from all affection to sin.”2

In doing so, you are not only sorry for the sin, but you resolve—through purifying yourself from your affections towards sin—to never sin again. In your spiritual life, both de Sales and the Catechism encourage us to make this resolve not imperfectly, out of fear of hell or punishment, but perfectly, out of our love for God (CCC 1452–53).

The next step is to confess your sin, either by scheduling a confession time with a priest or making use of the typical time for confessions at your parish. Take heart in the words of Pope Francis that “celebrating the Sacrament of Reconciliation means being enfolded in a warm embrace: it is the embrace of the Father’s infinite mercy.”3

The Catechism, following the Council of Trent, teaches that when we go to confession, “all mortal sins of which penitents after a diligent self-examination are conscious must be recounted by them in confession, even if they are most secret” (CCC 1456; cf. Council of Trent Session XIV.5).

If you are looking for further insight into the Sacrament of Penance, I recommend these wonderful books, especially the titles by Fr. Romanus Cessario and Dr. Lawrence Feingold, on the subject:

Naming Our Sins: How Recognizing the Seven Deadly Vices can Renew the Sacrament of Reconciliation

Price: $15.99

Once you have confessed all your known mortal sins to a priest and received absolution, you will be assigned a penance that will help you to make satisfaction for your sin and configure you to Christ. The Catechism explains that such penance might include “prayer, an offering, works of mercy, service of neighbor, voluntary self-denial, sacrifices, and above all the patient acceptance of the cross we must bear” (CCC 1460).

Having completed your penance, live out the words of our Lord, and “go and sin no more” (John 8:11).

What is a venial sin?

A venial sin, unlike a mortal sin, only weakens charity. Venial sins do not deprive the sinner of sanctifying grace. That is because, as St. Thomas points out “venial sin does not corrupt virtue as regards the habit (for this is proper to mortal sin).”4

There are two ways you might commit a mortal sin. Firstly, you could commit a venial sin if, in a less serious or grave matter, you do “not observe the standard prescribed by the moral law” (CCC 1862). An example of this could be gossip, which, while not necessarily falling into the full sin of calumny or detraction, nevertheless does not observe the standard of “you will not bear false witness” in its full moral sense.

Secondly, you might commit a mortal sin if you disobey “the moral law in a grave matter, but without full knowledge or without complete consent” (CCC 1862). An example of this would be if someone were to miss Mass because they thought a Mass was being offered at seven in the evening on Sunday, but that Mass was not offered that week. Missing a Sunday Obligation would be a grave matter, but you had every intention to go, and yet you missed it. In such a case, it is likely that sin is venial, though as with all sins it would come down to the particular circumstances.

At root, a venial sin “manifests a disordered affection for created goods; it impedes the soul’s progress in the exercise of the virtues and the practice of the moral good; it merits temporal punishment. Deliberate and unrepented venial sin disposes us little by little to commit mortal sin” (CCC 1863).

Venial sins should be avoided because they hinder our relationship with God; they dispose us to break off that relationship with God through mortal sin. That is why saints like St. Francis de Sales remind us that “you must not only cease to sin but you must also purify your heart of all affection for sin.”5

We are called to love God with all our heart, and that requires purifying even these small sins.

What if you have committed a venial sin?

Venial sins do not cause a loss of sanctifying grace, but they are a wound from the proverbial death by a thousand paper cuts. We all commit venial sins as an effect of original sin’s harm to our nature. And while not one of them can sever our friendship with God, many little sins taken together can dispose us to mortal sin, which does sever that relationship.

In order to work to overcome these venial sins in our lives and our affections for them, the Church encourages us to bring them up in frequent confession. By making use of the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation to help us overcome venial sins, the Church teaches that we “Form our conscience, fight against evil tendencies, let ourselves be healed by Christ and progress in the life of the Spirit. By receiving more frequently through this sacrament the gift of the Father’s mercy, we are spurred to be merciful as he is merciful” (CCC 1458).

What a gift God offers us in this sacrament! This is why Pope Francis encourages Catholics to make use of this sacrament: “The Sacrament of Reconciliation is a Sacrament of healing. When I go to confession, it is in order to be healed, to heal my soul, to heal my heart and to be healed of some wrongdoing.”6

Frequent confession offers our souls the regular healing we need to grow strong in our friendship with God.

Where can I learn more about sin and the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation?

1. The Catechism of the Catholic Church

There are many resources on the topics of sin and the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation, and first on that list is The Catechism of the Catholic Church. This text contains all the foundational teachings of the Church on any topic and contains extensive footnotes to help direct you to foundational primary texts on these topics.

2. The Seven Sacraments of the Catholic Church, by Fr. Romanus Cessario

If you are looking for a serious, academic, penetrating exploration on just about any theological topic, Fr. Cessario is an excellent teacher. In this text, he explains the theological meaning, historical development, and the reasons for the liturgical forms of each of the sacraments. His section on the Sacrament of Penance is extremely helpful in understanding the richness of this sacrament.

3. Touched by Christ: The Sacramental Economy, by Lawrence Feingold

Dr. Feingold currently teaches theology at Kenrick Glennon Seminary in St. Louis, and his experience as a teacher is obvious in his treatment of the sacraments’ historical development within the Church. For lay individuals who hope to learn more about the sacraments, or priests who want to brush up on their academic understanding of the sacraments in their theological development, Dr. Feingold is a rich source of insight on the Sacrament of Penance.

4. Naming Our Sins: How Recognizing the Seven Deadly Vices Can Renew the Sacrament of Reconciliation, by Jana M. Bennett & David Cloutier

If you want to understand more about how to classify sins (especially mortal sins) as you seek to grow and mature in your faith walk, this book by lay theologians Bennett and Cloutier is a must-read. It is so helpful in thinking through the traditional classifications in our modern experiences of life. Moreover, once we name sins, it is much easier to work on cooperating with grace to root the sins out of hearts as we seek to grow in our love for God.

- Jana Bennett and David Cloutier, Naming Our Sins: How Recognizing the Seven Deadly Vices Can Renew the Sacrament of Reconciliation (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2019), 15.

- Francis de Sales, The Introduction to the Devout Life, trans P. J. Tynan (Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son, 1885), 1.7.

- Pope Francis, General Audience: February 19, 2014. https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/audiences/2014/documents/papa-francesco_20140219_udienza-generale.html.

- Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Sentences (Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Academic, 2018), II.D42.Q1.A4.C3.

- De Sales, Introduction to the Devout Life, 1.7.

- Pope Francis, General Audience.