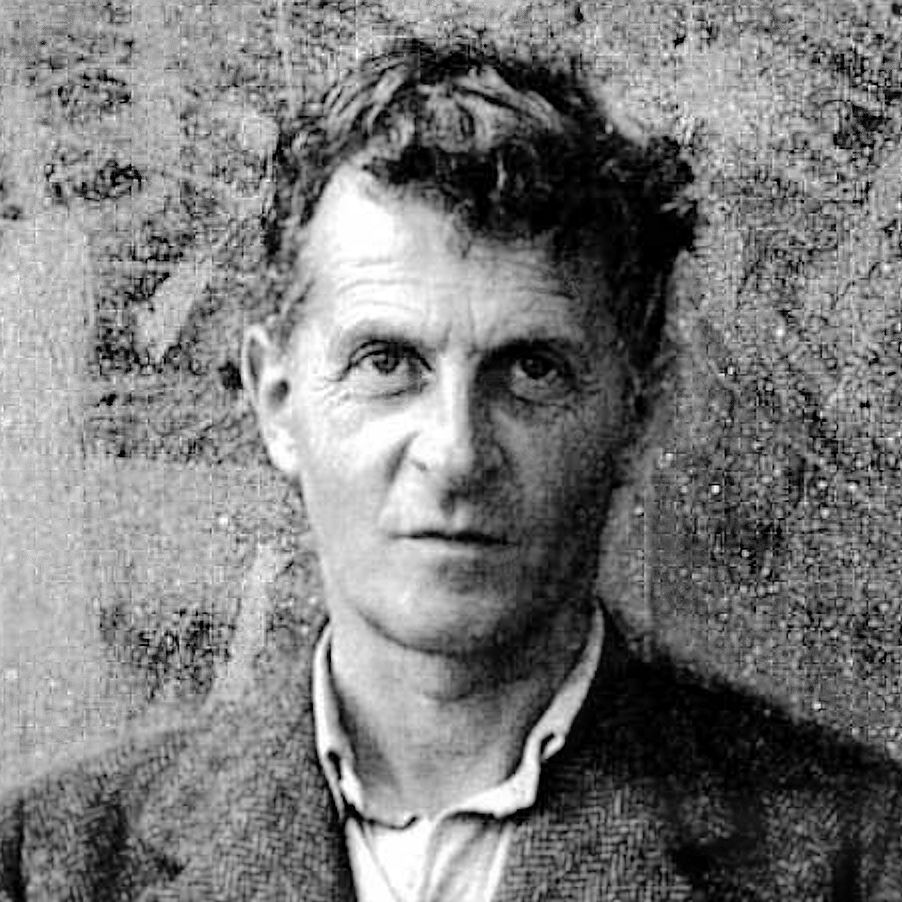

It will become evident that my debt is not only to Aquinas but also to a certain kind of modern interpreter. Once, largely through the work of Wittgenstein (1889–1951), the centuries-long domination of Western thinking by Cartesian and related empiricist doctrines had been broken, it became possible for philosophers to look back with a fresh understanding to pre-Cartesian thinking, in particular to Aquinas, and to discover how very congenial so much of his writing is to modern styles of questioning and answering. So I have been able to borrow shamelessly from Wittgenstein himself, but also from Elizabeth Anscombe (1919–2001), Peter Geach, Philippa Foot, Anthony Kenny, Alasdair MacIntyre and Gilbert Ryle (1900–1976) – though, perhaps, they (those of them still living at any rate) would not all acknowledge, or even recognize, their insights in the simplifications to which they have been reduced. This also means that what I have to say will sometimes seem strange to the older kind of ‘Thomist’ who was, I believe, often unwittingly influenced by empiricist or Cartesian presuppositions. So responses to my reflections and expositions are likely to take the form of arguments from many sides. But what other reason is there for writing any philosophical book?

Herbert McCabe, OP – The Good Life

The late Herbert McCabe, OP, longtime editor of New Blackfriars and author of many posthumously published books, was not typical of Dominican friars of his or later generations in that he paired his love of St. Thomas Aquinas with a keen interest in the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Wittgenstein had several prominent Catholic students. Foremost were Elizabeth Anscombe and Peter Geach, who arranged a Catholic funeral and burial for their teacher despite his never joining the Church. As McCabe writes above in his introduction to The Good Life, he read Wittgenstein as a way to reach beyond or beside the limitations of modern thinking and thus as a pathway to earlier thinking. Earlier thinking meant, chiefly, St. Thomas Aquinas.

McCabe shares with other philosophers in Wittgenstein’s lineage a clarity and playfulness of prose. He was relieved of his editing duties at New Blackfriars in 1967 for penning an editorial that criticized a former contributor for publicly leaving the Church. When he became editor again in 1970 he began his editorial, “As I was saying before I was so oddly interrupted…” Paul O’Grady notes that McCabe and Wittgenstein shared an absence of careerism and care for academic (and in Fr. Herbert’s case, ecclesiastical) decorum and self-advancement. Both chose a life of voluntary poverty. Neither published much in his lifetime, but each left an estimable (and now well mined) nachlass.

Not only inspired by both, McCabe charted the overlapping concerns of St. Thomas Aquinas and Wittgenstein: “When Wittgenstein in the Tractatus says “Not how the world is, is the mystical, but that it is”: (6.44) it seems to me that he is engaged with the same question as St Thomas when he speaks of esse.”

McCabe’s books and articles are free of philosophical or theological jargon—indeed, they are accessible always to any educated reader and often funny—so whatever one makes of his conclusions, his way of writing offers lessons in how to write and think about theology. (He shares these qualities with another Thomist whom we featured on this blog, Josef Pieper.)

Titles from Herbert McCabe, OP available in Verbum: