A guest post by Fr Andrew Dalton, LC (andrew.dalton@upra.org).

This post is the third in a series of guest posts in response to Dr. Mark Ward’s post on the LogosTalk Blog that addressed Pope Francis’s recent comments on the translation of the Our Father . The first guest post addressed the context of the Pope’s comments. The second, and the first part of this one, focused more directly on the Our Father.

“Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil” (Matt 6:13). The Our Father ends with one two-part request. What therefore God hath joined, let not man put asunder. This unity is good news for the interpreter. If the sixth petition seems enigmatic, the seventh sheds light on its meaning. To understand the whole, we will need to understand four principle parts: 1) lead into 2) temptation, 3) deliver, and 4) evil.

In my previous post, we explored the first key term, eispherō (to lead into). I argued that Scripture does not distinguish God’s active and permissive will. Especially in light of Matthew 26:41, it is likely that, for Matthew, “lead us not into temptation” is interchangeable with “do not let us enter into temptation.”

In what follows, I shall have to address several open questions:

- What does peirasmos mean: trial, temptation, or both?

- How does our answer affect our understanding of eispherō?

- The Catechism of the Catholic Church affirms that the Greek verb eispherō also carries the force of “do not let us yield to temptation” (cf. CCC 2846). Can such a position be defended?

- For Matthew, the Tempter is clearly Satan. Does the Father tempt us too?

- Why does the Father sometimes lead us into temptation?

- What does “but deliver us from evil” mean with regard to the sixth petition?

The Second Key Term: Temptation (peirasmos)

The noun πειρασμός (peirasmos) comes from the verb πειράζω (peirazō), which means “to test or to tempt.” Two basic concepts underlie one Greek word, so the sixth petition means, 1) “do not bring us into trial,” 2) “do not bring us into temptation,” or 3) “do not bring us into trial or temptation.”

Clarifying the Concepts

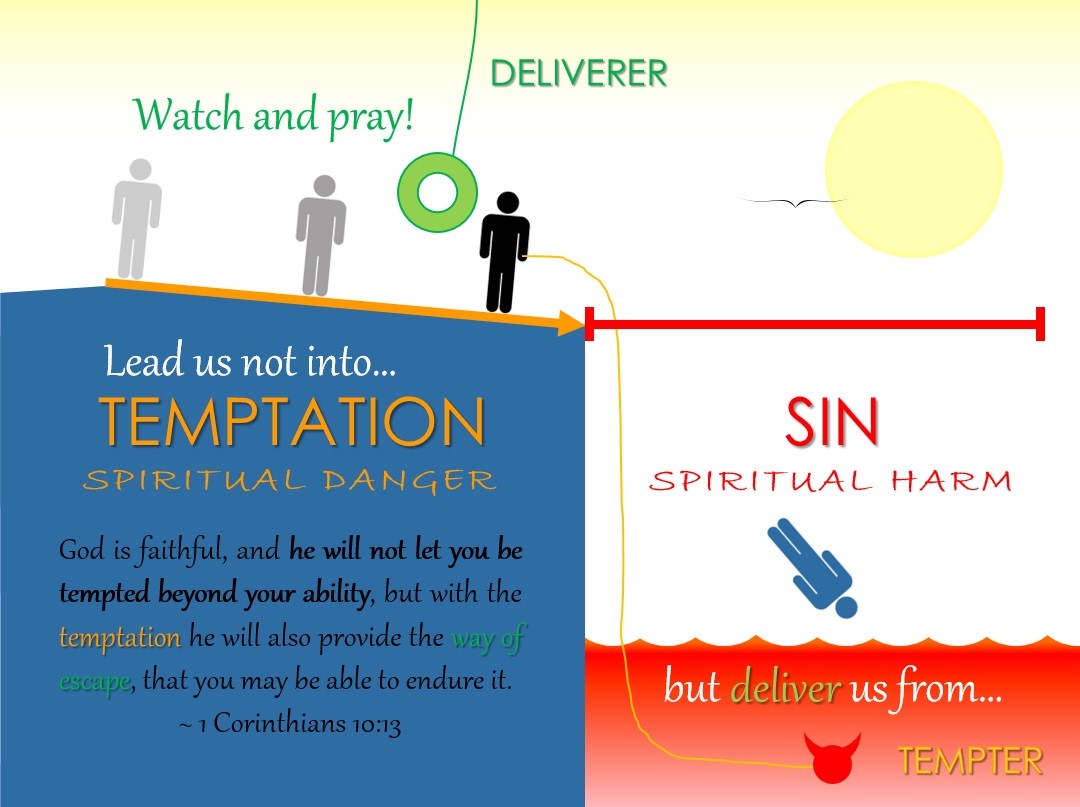

It is important to distinguish these terms. A “trial” refers to a source of suffering. A “temptation” signifies a specific type of trial (or test). Every “temptation” implies a trial, but not every “trial” implies a temptation. A “trial” has no necessary relationship to sin, but “temptation” means enticement to sin. To experience temptation is not to commit sin, but to consent to temptation is. Discovering your sister’s secret piggy bank is one thing; stealing it is another. Temptation is not a cause of sin, but it is an occasion of sin. (No, the devil did not make you do it, but he did make it easy for you to do!) An effect depends upon a cause, but the relationship between an effect and an occasion is not one of dependence (or contingency). Temptation can and often does result in sin, but not necessarily. Temptation is spiritual danger (cf. 1 Cor 10:13); sin is spiritual harm or death (1 John 5:16-17).

An illustration will help clarify these concepts further. Temptation is like a slippery slope leading to a lava pit. To sin is to plummet into the pit. Falling into temptation is one thing; falling after temptation is another. Temptation should not be conflated with sin, but the concept of sin is included in its definition. Whereas the word “trial” bespeaks a state of suffering, “temptation” is always referential (or better, intentional), like a vector with a known destination: unless you counter it, it will conduce to sin. If grace is the way to virtue, temptation is the way to sin.

The graphic above can be read allegorically. Man holds a string in his Hand, the other end of which the Tempter tugs, hoping Man will take the “way in” to sin. The Deliverer offers a “way out” (ἔκβασις, ekbasis, cf. 1 Cor 10:13): Man must unhand Temptation and cling to Grace. Which to choose? That is the question. All the drama lies in the Hand—a fitting symbol for the human will. “If you choose, you can keep the commandments” (Sir 15:13). The enemy can only harm those who give consent, just as God can only crown the one who “competes according to the rules” (2 Tim 2:5). Consent, then, constitutes the crucial line between virtue and vice, between victory and the fall.

The graphic also helps correct a misreading of the sixth petition. Translations like “do not let us enter into temptation”—and its close relative, “do not let us fall into temptation”—should not be taken to mean, “do not let us fall into sin,” except by way of a fortiori extrapolation. If we pray, “Do not let us take the way to Vegas,” then we have all the more reason to pray, “Do not let us arrive to Vegas.” Nevertheless, the words of these two expressions are not equivalent, nor do they carry the same force. Only by inference can we speak to the moment of arrival, for the moment mentioned was that of departure.

Matthew’s Iconic Peirasmos Passage

Matthew gives his own picture of peirasmos: the garden of Gethsemane illuminates the sixth (and seventh) petition. How does this portrait shed light on the notion of “entering into” peirasmos?

Jesus takes a small band of apostles to the garden, among them James and John. These same brothers once asked for a share in Christ’s glory, to which Jesus responded, “Are you able to drink the cup that I am to drink?” (Matt 20:22). He went on to say, “You will drink my cup” (Matt 20:22). When will they? Matthew’s readers did not have to wait long to know. Indeed, Jesus commanded that the disciples share in his cup just moments before getting to Gethsemane. At the Last Supper, Jesus took a cup, which he called “my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins” (Matt 26:28). Then, in the garden, the image of the cup reappears. Jesus prays, “My Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me” (Matt 26:39). Yet, this prayer he did not wish to pray alone.

Jesus told the disciples, “watch with me” (Matt 26:38). Again he instructed them, “pray that [ἵνα, hina] you may not enter into temptation” (Matt 26:41). Now, pious preaching has sometimes assumed that the disciples must watch and pray in order to console Christ. Perhaps that is part of his purpose, yet the reason Jesus gives is different. They must pray primarily for their sake, not his. Peirasmos is at hand, and unless they are vigilant and prayerful, they will enter into it.

But what does it mean to enter in? The circumstances clarify the answer. The disciples are seduced by sleep, again and again. As they enter into temptation, their peirasmos begins, but no fall is automatic or immediate. Jesus’ repeated pleas suggest that there is still time to escape what temptation tends toward—namely, sin—if only they would heed his voice.

Yes, Jesus brings his disciples to the slippery slope, as it were. One might say that he “leads” them into a place or period of peirasmos. In the measure they persist in slumber, despite divine exhortation, they are “yielding” more completely, “entering” more deeply into temptation.

Do Not Let Us Yield to Temptation

Reread in this light, “lead us not into temptation,” is not equivalent to “do not let us sin.” The expression, “in (times of) temptation, do not let us fall” is equally wrong. Falling “into” (εἰς, eis) temptation marks the beginning of a process; falling “in” temptation could mark the end of one (as in falling “when” tempted). In the Our Father, on the other hand, we pray, “do not let us yield an inch along the slippery slope; do not let us give the devil a chance to work on us (cf. Eph 4:27); do not allow us to take the way that leads to sin” (cf. CCC 2846).

Who is the Tempter?

Having analyzed two key terms (eispherō and peirasmos), we are better poised to consider the problem of the sixth petition: if “it is necessary that temptations come” (Matt 18:7), and if sometimes God does “lead into” the place of temptation (Matt 4:1), why does Jesus teach his disciples to pray, “Father, do not bring us into temptation?”

But does the Father tempt us? To answer, we have to put the key terms together.

Two actions (leading into and tempting) leave room for two agents (a leader and a tempter). Alternatively, one agent may accomplish both actions. Therefore, the sixth petition is open to two possible interpretations: (1) Father, lead us not into the place where you tempt us; or (2) Father, lead us not into the place where the enemy tempts us. Which interpretation is right?

Scripture clearly shows which interpretation is wrong. According to James 1:13, God himself tempts no one. The verb in that verse is πειράζω (peirazō). God is never the agent who entices someone to sin. That is not to say, however, that God never leads anyone into a time or place of enticement. In fact, God the Spirit did “lead” Jesus into the desert “to be tempted by the devil” (Matt 4:1). Yes, “tempted”—not “tested”—is the proper translation (pace Yaceczko), as the devil’s commands make clear (Matt 4:6, 9). If some commentators think it “absurd” that “one of God’s creatures could ‘tempt’ him,” it is because they fail to consider a Tempter who fails in a vain pursuit. Clearly, God led at least one person into temptation. Now, he is not the cause of the tempting, but he can be the cause of the leading in. Dr. Ward puts it simply: “God can lead us into temptation without being the tempter.”

This distinction has escaped some great minds. Donald Hagner argues that “testing”—not “temptation”—“is to be preferred because God does not lead into temptation (cf. Jas 1:13).” This is a non sequitur. Unfortunately, D. A. Carson and John Nolland use the same faulty reasoning. Moreover, James 1:13 does not say “God does not lead into temptation.” Rather, it says, “God tempts no one.” The mistake is to assume that the tempter must be the one who is leading into temptation. Once the non-necessity of this identification is noted, James 1:13 offers no support for “testing” in lieu of “temptation.”

To his credit, Dr. Ward avoids this error. Nevertheless, when he suggests that the Pope try the translation, “Do not lead us into hard testing” or “Lead us not into trials,” he does so by appealing to some commentators who use deficient reasoning to reach their conclusions. Now, those conclusions are true—i.e., we can rightly pray, “do not bring us into the test” (as Catholics in Hong Kong will attest)—because the word peirasmos carries this general sense, and because this is one dimension of the prayer’s meaning. (In passing, I should say that “testing” is preferable to “the test” since there is no article in Greek.)

There is no reason, however, to exclude the specific meaning (“temptation”). Et-et, non aut-aut. Moreover, the trial that we are most interested in not being led into is the trial of temptation. For this reason, the traditional translation is better than “testing” or “trial.” Whereas “hard testing” is directly associated with suffering, “temptation” is directly oriented toward sin. When facing the latter, we risk greater loss. The God who protects us from “testing” is big, but the God who keeps us from “temptation” is bigger.

If translators feel constrained to use only one word, “temptation” is better than “trial.” Still, the Italian adage is true: “traduttore, traditore,” which I (traitorously) render, “every translator is a traitor.” Every translation presupposes and presents an interpretation. Either translation of peirasmos—“trial” or “temptation”—reduces the semantic scope of the original word. To avoid limiting the original affirmation, we could pray, “lead us not into trial or temptation.”

We should pause to contemplate what this implies. If both words are viable translations—such that “trial” or “temptation” in the place of peirasmos would render a true statement—then God can lead us into trials and temptations. It is timely to mention that in Greek, “lead us not” (μὴ εἰσενέγκῃς, mē eisenenkēs), is an aorist subjunctive, not a present one. This may suggest that the one who prays is aware that God will not always keep away every temptation.

The toughest question is, “Why would our heavenly Father ever want to lead us into either trial or temptation?” The seventh petition will cast considerable light upon this confusion, but so will a Matthean metaphor for temptation. Let us begin with the latter.

Matthew’s Metaphor for Temptation

In this study, we are trying to surmise how Matthew understands the expression, “lead us not into temptation.” Ordinary prose is only one tool an author uses to describe reality, and so, in addition to peirasmos and peirazō, we should examine what synonyms and metaphors of temptation Matthew employs. What does his language show? Is there a difference between a cause and an occasion of sin? If so, which is temptation?

Matthew himself helps answer these questions, and modern translations have detected the answer. To explain how this is the case, first note some synonyms of “temptation.” Modern dictionaries list several: e.g. “enticement, attraction, seduction.” Matthew, however, uses none of these. Yet, in Matthew 18:7-8, he does use a figure: the “stumbling block,” (σκάνδαλον, skandalon) and its corresponding verb, “to make to stumble” (σκανδαλίζω, skandalizō).

An overly literal translation of this passage might read as follows:

Woe to the world from the stumbling-blocks! for there is a necessity for the stumbling-blocks to come, but woe to that man through whom the stumbling-block doth come! And if thy hand or thy foot doth cause thee to stumble, cut them off and cast from thee (Matt 18:7f, Young’s Literal Translation).

Most translations, however, rightly see in Matthew’s “stumbling block” a metaphorical reference to “sin” even though the word never appears: ta skandala are “temptations to sin,” and skandalizō is “to cause to sin.” Consider the ESV translation:

Woe to the world for temptations to sin [τῶν σκανδάλων, tōn skandalōn]! For it is necessary that temptations [τὰ σκάνδαλα, ta skandala] come, but woe to the one by whom the temptation [τὸ σκάνδαλον, to skandalon] comes! And if your hand or your foot causes you to sin [σκανδαλίζει, skandalizei], cut it off and throw it away (Matt 18:7f ESV).

Consider how Matthew’s metaphor reveals a truth about the causal dynamics of temptation. How does a “stumbling block” (skandalon) “cause” one to fall? Does a block of stone tackle the passerby? Does an inanimate object positively cause one to stumble? Obviously not. Granted, if placed in the middle of the road, such a stone makes it easy for one to fall. To be precise, it is the occasion, not the cause, of stumbling. This truth shines through in one Spanish translation of skandalizō: “And if your hand or foot is an occasion for you to sin, cut it off” (Si, pues, tu mano o tu pie te es ocasión de pecado, córtatelo) (cf. Matt 18:8 in the Biblia de Jerusalén Latinoamericana).

Notice what translators have recognized: 1) ta skandala can be rendered “temptations to sin,” even if the words are not literally equivalent; 2) this choice is justified because Matthew has described an occasion for falling, viz, a stumbling block that occasions one to trip; 3) therefore, translators understand “temptation” to be an occasion of sin.

One might object, “What about some translations that read, ‘And if your hand or your foot causes you to sin cut it off and throw it away’” (Matt 18:8)? Surely, temptation is seen as the cause of sin.

The conclusion does not necessarily follow. I have no contention with this kind of “overreach” precisely because hagiographers have a habit of dodging the distinction between the active and passive will. Given the scenario given by the evangelist, it is clear that this so-called “cause” is, in fact, no more than an “occasion.” If not, why do so many stones fail to result in a fall? Here, “cause” carries the force of “occasion.”

In this knowledge, “lead us not into temptation” is equivalent to “do not let us take the road riddled with the stumbling blocks,” i.e., “lead us not into an occasion of sin.” Strictly speaking, it is not equivalent to “lead us not into a cause of sin.” Even further removed is the expression, “do not let us sin.” These requests might be good, pious and salutary, but they are not what Matthew’s text has expressed, nor do they reflect his own understanding of temptation.

In passing, we should note a confirmation of the thesis presented in the previous post, namely that Scripture often uses active-will language where there is no active-will reality. The stone that “scandalizes” us does not scheme, much less execute, our fall, but it does sometimes occasion our collapse. Of course, many times we pass it by unscathed. There is no necessary causal relationship (contingency) between the effect (the fall) and the occasion (the stumbling block/temptation).

The Third Key Term: Evil (ponēros)

Let us segue out of the sixth petition and into the seventh—“but deliver us from evil”—which finishes the sentence. This commonplace nomenclature of “sixth petition” and “seventh petition” is a mere rhetorical convenience. Together they form one complete thought.

Since we have just examined peirasmos, which can have the broad meaning “trial,” it is timely to examine “evil,” which is similar. I find three Matthean synonyms of peirasmos, understood as “trial”: trouble (κακία, kakia), affliction (μαλακία, malakia), and evil (πονηρός, ponēros). This last word appears in the Our Father. What range of meanings does it have?

Matthew uses the word ponēros to refer to wicked people (Matt 5:39, 45; 12:34f; 13:49; 22:10), wicked thoughts (Matt 9:4), wicked dispositions (Matt 20:15), sickness (Matt 6:23), suffering (Matt 5:11), an enemy (Matt 5:38), or Satan (Matt 13:19, 38).

No single English translation can reproduce the rich ambiguity of the Greek: ἀλλὰ ῥῦσαι ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ τοῦ πονηροῦ, alla rhysai hēmas apo tou ponērou. “But deliver us from evil” is only one possibility of the text. The form πονηροῦ (ponērou) could be the genitive of the neuter πονηρόν (ponēron, evil), or it could be the genitive of the masculine πονηρός (ponēros, Evil One). Interestingly, the Nova Vulgata opts for the latter (sed libera nos a Malo, cf. Matt 6:13). Thus, there is another possible link between the peirasmos and ponērou: the “evil one” (cf. Matt 13:38) is called “the tempter” (ὁ πειράζων, ho peirazōn) only in Matthew 4:3.

For Matthew, then, the Tempter is clearly Satan. But could the Father be one too? Matthew does not explicitly answer this question, but we do find light in the New Testament.

God never wants our spiritual harm (sin) because he loves us, and “to love” means to will the good of another. Yet, God sometimes wants to expose us to spiritual danger (peirasmos) for the same reason (cf. Jas 1:2-4). To revisit a metaphor, God sometimes leads his people to the slippery slope, not to destroy them, but “that he might humble [them] and test [them], to do [them] good in the end” (Deut 8:16).

If it seems cruel for a father to treat his child in this way, we should recall Paul’s promise: “God is faithful, and he will not let you be tempted beyond your ability, but with the temptation he will also provide the way of escape, that you may be able to endure it” (1 Cor 10:13).

Paul explicitly recognizes a divine allowance. Apparently, God will let you to be tempted (cf. also Matt 4:1, 18:7), but “he will not allow [ἐάσει, easei] you be tempted beyond your ability.” Rather, he will supply you the grace to overcome temptation: “with the temptation he will also provide the way of escape.” Here, the emphatic adverb καί (kai), meaning “also,” suggests that God does leave room for the Tempter to operate, but not so much that the fall is inevitable.

Still, the fall is possible and, de facto, frequent. If this divine allowance results in our defeat, contrary to his intention, why does he allow it? To answer that question, we must analyze the last term, “to deliver.”

The Fourth Key Term: Deliver (rhyomai)

The verb “deliver” (ῥῦσαι, rhysai) comes from the verb ῥύομαι (rhyomai), which has two basic meanings: 1) to spare or 2) to rescue. Therefore, the seventh petition means, 1) “spare us evil/the evil one,” or 2) “rescue us from evil/the evil one,” or 3) “spare and rescue us from evil/the evil one.”

An illustration will help distinguish these two meanings of “deliver.” Two ships bound for London were boarding passengers—one in New York, the other in New Jersey. Hearing news of inclement weather, the captain in New York canceled his trip, and the passengers went home. The captain in New Jersey, however, decided to set sail. Two days later, a storm hit, and the ship sunk. A team rescued only one passenger. The story illustrates two ways of being delivered. The passengers from New York were spared the storm; in this way, they were delivered. Among the New Jersey passengers, none were spared the storm, but one was rescued. In other words, “spare” and “rescue” are two different ways of being “delivered.”

Deliver as Spare

Let us consider the first possibility, “deliver” as “spare.” The psalms certainly give a precedent for this meaning. “Behold, the eye of the Lord is on those who fear him, […] that he may deliver their soul from death and keep them alive in famine” (Ps 33:18f, cf. LXX). Many prayers for deliverance seem to envision the evasion of evil: e.g., “Deliver me from my enemies, O Lord! I have fled to you for refuge” (Ps 143:9). Now, if the enemy on the horizon happens to be the prince of demons, there will be especially strong incentive to pray, “Spare us the evil one,” i.e., “keep him far away!”

Deliver as Rescue

Sometimes, however, “deliver” does not signify “spare” at all. Consider Psalm 34:19 (cf. LXX): “Many are the evils of the righteous, but the Lord delivers him out of them all.” Obviously, one who experiences “many evils” cannot be “spared” them. In this context, “deliver” means “rescue,” and not “spare.”

Which meaning of “deliver” best fits the Our Father: “spare,” “rescue,” or both? The answer will need to accommodate the adversative conjunction, “but” (ἀλλὰ, alla), that begins the seventh petition.

Accommodating Alla

“Lead us not into peirasmos, but (alla) spare us evil.” Does this formulation make sense? Not really. The first and second halves are too similar to make sense of the adversative conjunction, which signals some sort of antithesis. If this were the best reading, another conjunction would work better: “keep us from peirasmos,” and “keep us from evil.” I suspect this misreading lurks behind the Spanish mistranslation, “and deliver us from evil” (y líbranos de mal).

If ponēros means “the evil one,” however, “spare” could make sense of the conjunction. To explain, imagine two doors: behind the first one lies testing/temptation, behind the second one, Satan himself. You might be inclined to pray, “Father, lead me not into door one, but—please, please—spare me door two!” In other words, the adversative conjunction could contemplate a “worst-case scenario” (cf. France).

Though logical, I doubt this is the primary meaning of the seventh petition. We must consider the possibility that “deliver” means “rescue.”

“Rescue us from evil/the evil one” makes much better sense, especially in light of our analysis of temptation. Temptation is the occasion of sin, and de facto often leads to sin. Temptations must come (cf. Matt 18:7), and we might yield to them, fall down, or even die spiritually (cf. Luke 15:24; Col 2:13; 1 John 5:16). We might commit all kinds of ungodly sins, but hope should never die. For “the Deliverer will come from Zion, he will banish ungodliness from Jacob; and this will be my covenant with them when I take away their sins” (Rom 11:26).

The seventh petition, therefore, goes beyond the notion of protection from peirasmos and even addresses sin. In this way, the seventh petition extends and intensifies the meaning of the sixth. One very important dimension of the seventh petition (unmentioned by the sixth) echoes the prayer of the psalmist, “Deliver me from all my transgressions” (Ps 39:8). As seen above, if the sixth petition can reach this idea at all, it is only by way of inference, i.e., a fortiori extrapolation.

In sum, the sixth and seventh petitions convey the following: “Father, lead us not into peirasmos, but (if it is not possible, given that some temptation must come) rescue us from evil/the evil one.” This reading accounts best for the adversative conjunction that binds the sixth and seventh petitions together. Therefore, the seventh petition is best taken to mean, “Father, if and when we find ourselves in any spiritual danger, whether hard testing or temptation, rescue us from whatever risk remains and from whatever damage is actually done.”

“Rescue us from evil/the evil one” also makes better sense in light of Christ’s own story.

In Gethsemane, Jesus Taught Us to Pray, “Rescue Us.”

Jesus’ own life story lends further support to the idea that “deliver us” in the seventh petition means “rescue us” more than “spare us” (though the worst-case scenario remains one possibility of the text). He taught his disciples how to pray not only with his words, but also by his behavior.

In Gethsemane, Christ commanded Peter to pray that he may not enter into peirasmos. Yet, the Father did not spare Jesus death-like sorrow or the fury of the cross, despite his prayer. “My father,” he prayed, “if it be possible, let this cup pass from me” (Matt 26:39). Jesus’ request parallels the seventh petition. Now, as we have seen, “but rescue us from evil” follows a tacit recognition that some peirasmos must come, i.e., that it is not always possible to be spared every storm. Jesus recognizes this fact quite explicitly when he adds, “nevertheless [πλήν, plēn], not as I will, but as you will” (Matt 26:39).

One Matthean redaction of Mark’s Gethsemane pericope is especially worth noting for our study. In Mark, Jesus prays, “Yet not what I will, but what you will.” (Mark 14:36; cf. Matt 26:39). Matthew alters his source in such a way that his readers hear more easily an echo of the Our Father. Only in Matthew does Jesus add, “My Father, if this cannot pass unless I drink it, your will be done” (Matt 26:42). This redaction may give us a window into Matthew’s mind.

Matthew’s reference to the final “thou-petition” (cf. Matt 6:10b) endorses the methodology of juxtaposing and comparing these two pericopes, that each may be interpreted in the light of the other.

Matt 6:10 γενηθήτω τὸ θέλημά σου

Matt 26:42 γενηθήτω τὸ θέλημά σου

Given the verbatim phraseology, it is likely that Matthew interpreted the Our Father in light of Christ’s agony. Moreover, it underscores the inexorable unity of the Lord’s Prayer, from beginning to end. Ever trustful in his Father, Jesus endured peirasmos (and even physical death), but the Father did not deny the anguished supplications of his son. Jesus knew he could always appeal to his Father (cf. Matt 26:36). As the author of the Letter to the Hebrews makes clear, early Christians read the agony in just this light: “[Jesus] was heard because of his reverence” (Heb 5:7).

Yet, one might ask, if Jesus’ prayer was accepted by the Father, why then was he not delivered from the cross?

He was! He just was not spared. Rather, he was rescued. God raised him from the dead (cf. Matt 28:6). For Jesus, “deliverance” meant post mortem resurrection.

What a sobering truth for every disciple who takes up the Lord’s Prayer!

Conclusion: Praying the Our Father with Matthean Minds

In the sixth petition, we ask for protection from temptation, not to enter into it, not to yield to its seductive power. Moreover, we ask to be kept far away from trial, aware that we will not be fully spared—and in this, the prayer of the disciple parallels Christ’s. And we finish the thought with a request for rescue from spiritual danger and deliverance from spiritual death (the seventh petition). In this way, our two-part petition parallels our Lord’s prayer in the garden.

If Christ endured trial and temptation (cf. Heb 4:15), even a cruciform peirasmos, and if he is “the Way, and the Truth, and the Life” (John 14:6), then we who are his followers must be ready “to take up [our] cross” (Matt 16:24). Indeed, our whole life in this world is peirasmos (cf. Job 7:1), and Jesus prayed, not that the Father “take [us] out of [it], but that [he] keep [us] from the evil one” (John 17:15). Per crucem, ad lucem!

To conclude, let us summarize the general sense of the Lord’s perfect prayer, as given by the Gospel of Matthew, having studied it in context.

Heavenly Father, spare us trial, temptation, and the evil one. But, if you see fit that we be exposed to some spiritual danger, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Do not let us enter into temptation. Some trials and temptations are bound to beset us, yet not one which you do not allow. If we do yield an inch along the slippery slope of temptation, rescue us before we fall. If we fall, then deliver us from our sin.

Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen.

Fr. Andrew Dalton, LC teaches Biblical Greek and Hebrew while pursuing doctoral studies at the Pontifical Athenaeum Regina Apostolorum in Rome. He obtained a licentiate degree in Biblical Theology from the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross and a post-graduate certificate in Shroud Studies. A board member of Othonia, he lectures internationally on the Turin Shroud and The Biblical Theology of the Passion for the Science and Faith Institute in Rome.

Fr. Andrew Dalton, LC teaches Biblical Greek and Hebrew while pursuing doctoral studies at the Pontifical Athenaeum Regina Apostolorum in Rome. He obtained a licentiate degree in Biblical Theology from the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross and a post-graduate certificate in Shroud Studies. A board member of Othonia, he lectures internationally on the Turin Shroud and The Biblical Theology of the Passion for the Science and Faith Institute in Rome.

Two basic concepts underlie one Greek word, so the sixth petition means, 1) “do not bring us into trial,” 2) “do not bring us into temptation,” or 3) “do not bring us into trial or temptation.”

Why not 4) “do not bring us into trial and temptation”? Wouldn’t it be a fairer use of the word to apply both senses? For not all trials lead to temptation and not all temptations are trials (like being tempted to turn stones into bread when we are full). We are praying to avoid those trials that lead to temptation (like being tempted to turn stones into bread after not eating for 40 days) and those temptations that are trials. Since God would only lead us to these temptations to try us (anything else would just be sadistic), then trials, rather than temptation, still seems to better capture the sense of the petition.

O good, a grammar question! Those are always fun. We agree that both senses apply to peirasmos: it means “trial” and “temptation.” In the sixth petition, we pray, “Do not bring me into trial” AND “Do not bring me into temptation.” To combine those two clauses into one compound sentence, we must use OR: “Do not bring me into trial OR temptation.”

If you combine the two clauses using AND, it means something different. Here’s an example, “Dad, do not bring me to NY AND LA.” Dad could respond, “Okay, I’ll bring you just to LA. Or else, I’ll bring you just to NY. But, I won’t bring you to both since that’s what you asked.”

In the Our Father, we pray to be protected from ALL “temptation,” whether especially “trying” or not. St. Augustine has an unforgettable chapter in his Confessions about just this phenomenon. He steals some pears, not because he is particularly seduced by them, but just because he can. Temptation that does not feel very seductive subjectively is temptation nonetheless.

Now, “Do not bring us into trial” is one dimension of the sixth petition. Nevertheless, it is only one dimension of the prayer. The problem with this translation is not what it says; it’s what it leaves unsaid (to most ears).

In virtually every time and place, the Church has preferred to translate the Our Father with “temptation,” despite her knowledge of “test” as a legitimate alternative. Personally, I doubt the Holy Spirit has dropped the ball.

Finally, keep in mind that suffering is not only for our growth in virtue. Mary suffered, not because love was lacking, but because she was given the grace to share in Christ’s redemptive death (cf. Luke 2:35). Christ suffered, not because he needed it to become better, but because he wanted to manifest perfect, saving love. A God who permits us to suffer is not sadistic; rather, he offers us the chance to unite ourselves to him. In Paul’s words, we “fill up what is lacking in the sufferings of Christ for the sake of his body, that is, the Church” (Col 1:24).