This time of year, children ask, “Is Santa Claus real?” And my instinctive response is: Yes! He was a fourth-century bishop in modern Turkey. He goes by many names: Weihnachtsmann, Sinterklaas, Dun Che Lao Ren, among others. You may know him as Santa Claus. But he first went by Nicholas of Myra. On December 6, Catholics, Orthodox, and many Protestants all over the world join in celebration of the Feast of Saint Nicholas, or Nicholas Day.

But this invites a new question: Was there really a Nicholas of Myra?

- Was there really a Nicholas of Myra?

- From St. Nicholas to Santa Claus

- St. Nicholas vs. Santa Claus

- How did St. Nicholas become associated with Christmas?

- What did St. Nicholas look like?

- Conclusion

Was there really a Nicholas of Myra?

This is an earnest question for Catholics. St. Nicholas, while still ranking among the most widely known saints, is less popular today than he has been for most of Catholic history, if you can believe it. After over a millennium celebrating his Feast Day, the 1969 edition of the Roman Catholic calendar of saints demoted Nicholas Day to the status of “optional.” The reason was his existence had come increasingly into doubt. Beginning in the early twentieth century, historians began to speak of the stories about Nicholas as “almost certainly legends.”1 Within decades, they began to wonder if Nicholas wasn’t a legendary figure altogether.

And who could blame them? Nicholas left no writings and none of his contemporaries wrote of him. He played no major role in either imperial or ecclesial politics. His name appeared in some, but not all, of the lists of those who attended the Council of Nicaea in 325. And if he attended, he made no major contributions to the proceedings. (The story of him punching Arius at the council does not appear until the fourteenth century.) Worst of all, no contemporary witness in the extant historical record testifies to Nicholas’s existence. If he had friends among other bishops, they never mentioned him in their writings.

Patron saints, however, occasionally have “patron” scholars. Or so we could describe Father Gerardo Cioffari (b. 1943), a humble Dominican friar and head curator of the archival library of the Basilica di San Nicola in Bari. Despite the scholarly consensus, Fr. Cioffari wasn’t ready to deny the existence of a historical St. Nicholas. He spent thirty years sifting through the artifacts and manuscripts stored in the archive, and eventually unveiled new evidence of the saint’s existence as well as of many of the deeds associated with him. Fr. Cioffari believes Nicholas lived approximately from 260 to 335, and most likely did attend the Council of Nicaea, representing Myra.

Before Fr. Cioffari published his research, the earliest mention of Nicholas that could be dated with confidence came from the imperial historian Procopius in the year 555, reporting the building of a shrine to St. Nicholas in Constantinople, present-day Istanbul, Turkey.2 Fr. Cioffari uncovered additional sources that push references to St. Nicholas earlier in the historical record. Among these is the Encomium of Proclus, which includes a speech praising the many virtues of St. Nicholas dating to roughly the year 440—over a century earlier than Procopius. Interestingly, the Encomium clearly draws its information about Nicholas from an even earlier source, a Greek biography of St. Nicholas.3 Though this biography is now lost, knowledge of its existence pushes St. Nicholas even further back in the historical record, nearing the time he is said to have lived.

Of the other sources uncovered by Fr. Cioffari, one more bears mentioning: the Tripartite History of Theodore the Lector, which names St. Nicholas of Myra as one of the attendees at the Council of Nicaea. As it turns out, of the sixteen extant lists of attendees of the Council of Nicaea, Nicholas’s name is missing from ten. Each list differs in the number and names of attendees.

For some time, it was believed the shorter lists—which record around 200 names—were the older and more reliable ones, whereas the longer lists—clocking in around 300 names—were less so. This can no longer be taken for granted, however, since some figures who are known to have spoken at the council, such as Paphnutius, an Egyptian bishop, are not mentioned in the shorter lists, but do appear in the longer ones. There could be many reasons for the disparities between the lists. It could be that the longer lists recorded attendance at later sessions, after more bishops from farther reaches of the empire had opportunity to arrive.

In any case, St. Nicholas appears in the six longer lists that record 300 or more attendees. Among these six is the list compiled by Theodore the Lector in 515, which is by far the most important of all the lists since he had access to the best and most complete information available at the time. Historian Adam English explains his position as lector (anagnostis) or “reader”’” of the church at Constantinople perfectly situated him “to gather, trade, and investigate information regarding historical and ecclesial questions”—a situation which makes his account particularly valuable and led to his commission to compose an ecclesiastical history, Tripartite History.4 Number 151 in his list: Nicholas of Myra.5

Other evidence has since corroborated the likelihood of a historical St. Nicholas.6 While no evidence offers us certainty, it seems more likely now that there really was a St. Nicholas than that there wasn’t. This being the case, what can we say about him? Very little, but even so: He was bishop of Myra during some of the most interesting times of Christian history. He survived the Diocletian persecution—the last and bloodiest of the persecutions—and witnessed the vitalization of the Church under Constantine. He in all probability attended the Council of Nicaea (fashionably late?) but did nothing to report. He was likely born to wealthy Christian parents in the Lycian city of Patara, in modern-day Turkey, and he died in the early fourth century.

From St. Nicholas to Santa Claus

How did an obscure bishop—evidently not worth mentioning by his contemporaries—manage to become one of the most famous saints of all time? And how did this saint then become Santa Claus?

As mentioned earlier, one of the earliest references (for a while, the earliest reference) to St. Nicholas comes from the imperial historian Procopius, in the year 555. Procopius reported the construction of a shrine to St. Nicholas. The shrine protruded over the Sea of Marmara. Its placement was not meant to charm pilgrims with a seaside vista, but to make itself visible to passing sailors. Procopius’s history reveals two things:

- The fame of St. Nicholas had traveled from his hometown and reached Constantinople, the capital of the eastern Roman Empire, by the mid-sixth century, but likely earlier.

- St. Nicholas’s early fame was not connected to gift-giving or Christmas but to seafaring. Sailors invoked his name for safe passage, and boats often included niches to store icons or miniature statues of the saint. English reports another custom: “Nicholas loaves [of bread] were kept on board so they could be tossed into the churning waters at the first sign of bad weather; some sailors did not bother to wait for trouble but threw out three small loaves upon embarkation to ensure safe travels.”7

As sailors, fishermen, and sea-merchants crisscrossed the Mediterranean, they brought with them stories, images, and endorsements of St. Nicholas, the protector of those who travel by sea. This connection to seafaring does much to explain the rapidity with which St. Nicholas’s cultus spread throughout Europe.

Stories of St. Nicholas did not only spread by word of mouth. His earliest surviving hagiography was written nearly half a millennium after his death by Michael the Archimandrite around AD 700 or 710. In the late-800s, John the Deacon translated this hagiography from Greek into Latin from his home in Naples, Italy, and thus introduced St. Nicholas to the West. About a hundred years later, Reginald, Bishop of Eichstätt (d. 991), supplemented John’s translation with several new stories and miracles from his home in Bavaria, Germany. One of these additions would become a favorite subject of later Western painters: the rescue of Adeodatus, wherein a long-deceased St. Nicholas appears just in time to rescue a kidnapped child, Adeodatus, by gripping his hair and flying off to return him to his parents.

By the Renaissance, St. Nicholas was one of the most popular saints in Europe. But then came the Protestant Reformation, which erased St. Nicholas from great swaths of Europe. He would be replaced in Victorian England by the more archetypal Father Christmas, who was thought safer since he had no connection to the cult of the saints. In the eighteenth-century, Dutch Catholic settlers (re?)introduced this great saint to Protestantism in New Amsterdam. After the revolution, Americans were hungry for alternatives to English culture, and Washington Irving and John Pintard were both fascinated by the Dutch settlements in New York, and in particular their celebration of the Feast of St. Nicholas. They published multiple articles, poems, and stories in The Sentinel featuring “Sinterklaas” (a shortened form of Sint Nikolaas, the Dutch for Saint Nicholas), a name which would eventually be Americanized into Santeclaus,8 then Santa Claus.

By all accounts, the line from St. Nicholas to Santa Claus is more direct than many realize. As far as names go, Santa Claus is St. Nicholas, and his early emergence in American holiday culture is sourced in the cultic devotion of Catholic immigrants.

St. Nicholas vs. Santa Claus

As we have seen, it is difficult to make any definite statements about the historical St. Nicholas. We must admit that the St. Nicholas we know from tradition is more legend than history, however real a basis that legend may have in history. The earliest biographical details about him appear in Michael of Archimandrite’s hagiography written nearly half a millennium after his death. Adding to the confusion, he is often mistaken in the record for Nicholas of Sion. The two share a name and an association with seafaring, but they lived two centuries apart, yet later biographers would often combine the two into one. As his popularity grew over the centuries, new stories and accessories were added, and St. Nicholas accompanied a broader range of associates, depending on the region: such as the horned Krampus in Bavaria or the soot-blackened Zwarte Piet (“Black Pete”) in the Netherlands. At the height of his popularity, there were almost as many Nicholases as there were countries in Christendom.

Every December, we enjoy drawing sharp distinctions between the “traditional” St. Nicholas and the “commercial” Santa Claus, but historical honesty forces us to admit there are many Nicholases, not one “traditional” Nicholas. The American version (for that is what Santa Claus is) was simply another one of these. So rather than speak of the “historical” Nicholas or attempt to depose our native version as an imposter, I’d rather identify the strains of continuity between the legend of Catholic hagiography and the legend of American fireside storytelling. Santa Claus, I contend, is simply the American St. Nicholas, and a more faithful iteration than we might at first realize.

This isn’t to deny there are stark differences. Putting aside the sleigh, reindeer, elves, and a toy factory in the North Pole, St. Nicholas’s earliest biographer portrays him as a natural ascetic. As a nursing baby, he took milk only once a day on Wednesdays and Fridays, as these were the traditional days of fasting. “The blessed child adhered to the sacred observances regarding food,” observed Michael, “revealing even then a pure and holy heart.”9 Medieval preachers would remark on this story to show how Nicholas even in infancy “reigned in the vice of gluttony.”10 Contrast this with Santa’s fondness for milk and cookies which endows him with a “little round belly” that “shook when he laughed like a bowlful of jelly.”

Yet there are aspects of the modern Santa Claus that remain faithful to the St. Nicholas venerated by Catholics, particularly his reputation as a clandestine gift-giver, as found in the most famous traditional story. As Michael the Archimandrite tells it, a father became so financially desperate he resolved to sell each of his three daughters, one by one, into prostitution—a regrettably common recourse in the ancient world. The prospect pained the father greatly, but since he could not afford dowries for his daughters, no suitor would take them. To him, prostitution was preferable to destitution: at least this way, the girls would have means to live. The night before he was to sell his first daughter, a bag of money in exactly the amount needed for a dowry appeared on the floor of his home overnight. It had been tossed through the window while he slept. In later versions of the story, the money was thrown down the chimney or stuffed inside stockings hung over the fireplace to dry. The father couldn’t believe his fortune! He married off the daughter immediately. The next night, another moneybag appeared for the second daughter, and he married her off, too. On the third night, the father was ready. Eager to identify his patron, he kept vigil so when he heard the clatter of coins on the floor, he dashed out the door and tackled the backwards-burglar. It was none other than his own bishop, Nicholas—who pleaded that his good deed be kept a secret. Instead, this story found such fame, it became St. Nicholas’s calling card: to pick him out in an icon of mitred saints, you need only look for the bishop holding three moneybags (or three gold spheres or saucers). Here we see the theme of the covert night-time gift-giver has survived up to today’s Santa Claus.

How did St. Nicholas become associated with Christmas?

Michael the Archimandrite might give us the earliest reference to the celebration of Nicholas Day in the introduction of his hagiography, though by the time of his writing, people had been apparently celebrating his feast day for some time. Michael indicates this celebration was occurring as the Church was preparing “for the coming of God’s Word according to the flesh from the holy Virgin.”11 While the precise date for Nicholas Day is not given, it clearly approximates the season of Advent, and there is no reason to suppose it wasn’t December 6, as all Christian traditions testify.

At any rate, Michael’s biography shows us that Nicholas was associated with Christmas at an early point, as he was the first great saint the Church encountered on the road through Advent. Michael commends his veneration, calling Nicholas “a help in danger and the defender of those living in various tribulations,”12 so already the saint’s charitable and gift-giving character was established and set a model for the season ahead. No doubt Nicholas’s virtues assisted his connection with Christmas, but the material cause was serendipitous: he just happened to have died near the start of Advent.

What did St. Nicholas look like?

We all know the modern image of Santa Claus: the wide snowy beard, knobby nose, the red suit with white fur trim and matching stocking cap, the broad black belt, and a portly but grand figure. This image came together in the advertising art of Haddon Sundblom, a cartoonist hired by the Coca-Cola Company in the early twentieth century. Coca-Cola was eager to boost winter sales and rehabilitate its image after suffering criticism from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. The temperance movement not only objected to liquor, but to any “drugged” (that is, “any mood- or behavior-modifying”) libation that, in their view, promoted degeneracy. In the case of Coca-Cola, the objection was its caffeine content.

Today, we might think it absurd to place a Coke in the same category as a glass of port wine, but after thirty years of Norman Rockwell-esque advertisements depicting lush Christmas scenes on magazines and billboards, Coca-Cola gained the reputation of a “Christmas beverage” and their warm, reassuring version of Santa fixed itself in the popular imagination. Virtually all later depictions of Santa Claus in popular media and advertising up to the current day—from lawn decorations to movies like Elf (2003)—are descendants of the Sundblom Santa.13

So what did the traditional St. Nicholas look like? Michael provides the earliest physical description of St. Nicholas’s appearance: the saint fully embraced the vocation of a bishop to live humbly and simply, surpassing his fellow bishops in this respect. He did not wear embroidered silk robes, gold chains, or white gloves. He even forewent his seal of ecclesial authority: his signet ring! He favored a simple, cheaply made black garb.14 He looked less like a bishop than a peasant.

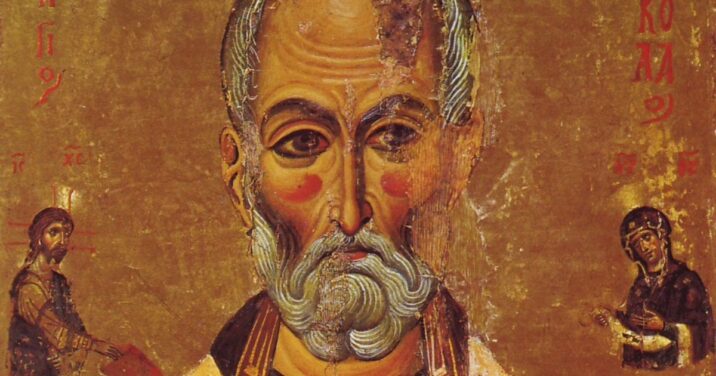

The earliest artistic representation of St. Nicholas comes a little closer to the modern image we recognize. This is found in an icon whose creation dates sometime between the mid-600s and the mid-700s, so it was likely contemporaneous with Michael’s biography. This icon is stored today in the Monastery of St. Catherine in Egypt. Nicholas’s beard is white, but long, straight, and pointed—like a paintbrush. A halo encircles his white head. He wears festive Byzantine-style vestments of red and gold. Lobate crosses dot his omophorion (i.e., the traditional article draped over the neck and shoulders that symbolizes the lost sheep carried by the good shepherd in Jesus’s parable in Luke 15:3–7). His left hand holds a book; his right is raised in blessing.15

So, what did St. Nicholas look like? A bishop.16 And so he would always be depicted. When Roman bishops began to wear miters in the eleventh century, and swing curly croziers in the thirteenth, contemporaneous icons and paintings of St. Nicholas updated his wardrobe accordingly. Religious art in the ancient and medieval worlds was always contemporaneous with its original audience in terms of fashion, so St. Nicholas’s image, in this respect, was inconsistent precisely because it was consistently of a bishop.

As much as we might resent the dominance of “Kitsch” Kringle, we must admit he resembles the traditional St. Nicholas more than his predecessors. The earliest popular American depictions of Santa cast him as an imp. Thomas Walter Weir’s painting St. Nicholas (c. 1837), for example, features a goblin-like creature in a red cape. He is cackling over his shoulder, presumably about to scurry up the chimney. Using the hearth for scale, it appears this St. Nicholas is barely three feet tall. Clement Clark Moore’s winsome poem “’Twas the Night before Christmas” (1823) is another watershed piece of media for the character’s image, wherein he is described as “a right jolly old elf.” Finally, Thomas Nast, a late-eighteenth century cartoonist who popularized depictions of Santa as a heavyset person who drove a sleigh harnessed to reindeer, favored a wily home invader slinking around furniture in red pajamas, a mischievous smile behind a wispy beard and, again, a stature not much greater than a child’s. (Nast may also be responsible for popularizing the idea that Santa Claus lived in the North Pole.)

Today’s Santa Claus is a larger-than-life character of boundless mirth, a permanent grandfatherly smile, and a deep staccato laugh. He’s less an elf than a yuletide Paul Bunyan. (In fact, he seems to sit more comfortably in the American tall-tale tradition than in Old World nursery rhymes.)17 Though he remains a far cry from the model of holiness presented in ancient hagiography, even so, Santa has come to resemble St. Nicholas more and more over the years, not less. And as much as we might resent it, the Sundblom Santa is to credit for this. Sundblom, the son of Scandinavian immigrants, consulted his Swedish and Finnish heritage for reference when designing his version of Santa for the Coca-Cola Company. So, ironically, the Sundblom Santa, despite being technically an artifact of corporate art par excellence, is a (albeit modestly) reformed Santa.18

Conclusion

The story of scholarship in the last half-century has only strengthened tradition’s commendation of St. Nicholas of Myra. Perhaps it is time for Catholics to revive the jolly seriousness Nicholas Day once called for. He is a rare saint in that he is non-biblical yet is universally venerated in both East and West, and even in some corners of Protestantism. He is, in this sense, truly catholic (i.e., “universal”).

What is more, the emergence of Santa Claus is a credit to early American Dutch Catholics who maintained the observance of Nicholas Day. This makes Santa Claus unique, for it means he is America’s last culture-wide link—perhaps the only link of its kind—to Catholicism’s life of cultic devotion. In the end, Santa Claus is Protestant America’s only popular saint (with the possible exception of St. Patrick of Ireland). We should consider whether there is something worth preserving there, and something worth believing in.

Be your own Secret Santa

- Thomas Craughwell, Saints Preserved: An Encyclopedia of Relics (New York: Image Books, 2011), 220.

- Procopius, De aedificiis 1.6, in Procopius, trans. H. B. Dewing, Loeb Classical Library 7 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1935), 62–63.

- Gerardo Cioffari, S. Nicola nella Critica Storica (Bari: Centro Studi Nicolaiani, 1987), 17–21.

- Adam C. English, The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus: The True Life and Trials of Nicholas of Myra (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2012), 16.

- Cioffari, S. Nicola, 23–29.

- See the physical evidence published by Dutch scholar Aart Blom, Nikolaas van Myra en sijn tijd (Hilversum: Verloren, 1998). For a survey of the available evidence for the historical Nicholas of Myra, see English, Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus, 10–18.

- English, Saint Who Would Be Santa, 174.

- “Old Santeclaus with Much Delight” is a children’s poem published anonymously in New York in 1821.

- Michael the Archimandrite, Vita per Michaelem, 4, quoted in English, Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus, 33.

- Quoted in Charles Jones, Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 51.

- Michael, Vita per Michaelem, 1, quoted in English, Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus, 28.

- Michael, Vita per Michaelem, 1, quoted in English, Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus, 28.

- Though quintessentially American, this Santa soon went international. The British Father Christmas, who has his origins in English folklore as a sort of personification of the wintry season—and no actual connection to St. Nicholas—had been assuming Santa-like attributes for decades. By the early twentieth century, the two were spoken of interchangeably. (G. K. Chesterton’s essays are a good case in point.) Once Santa’s American image was fixed, traditional representations of Father Christmas in Britain became scarce and took on an “old-fashioned” air, though they continued to refer to Santa Claus as Father Christmas.

- Michael, Vita per Michaelem, 24.

- For image and description, see English, Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus, 6. Nicholas shares the icon with three other saints: Paul, Peter, and John Chrysostom. The monks who painted this icon must have had the highest regard for Nicholas to place him in such company.

- The real disparity between traditional representations and the Sundblom Santa is the latter’s divested. He’s a saint in a suit. In short, he’s a Protestant.

- In fact, I’d contend this is the real difference between Santa Claus and St. Nicholas: one is an American tall-tale, the other is a legendary model of holiness.

- At times in history, these images of St. Nicholas and Santa Claus would compete for dominance. One such wrestling match took place in the town center of Demre, Turkey, at the start of the millennium. Demre is modern-day Myra: St. Nicholas’s home-town. In 2000, a bronze statue of St. Nicholas was put on display. A gift from Russia, the saint is balanced atop a globe, complete with liturgical vestments, a Bible, a halo, and a hand raised in blessing. Russian pilgrims to the city regularly knelt or bowed before the image. Five years later, the town council decided to replace the statue with a smiling, brightly colored, all-American Santa Claus. He hefted a bulging bag of gifts over one shoulder; his free hand brandished a bell like a Salvation Army ringer. In a country that is nearly entirely Islamic, the decision was intended to boost tourism. Evidently, it did not meet the bottom line, and Jolly Old St. Nick was taken down after just three years. In his place today stands a patriotic young man cast in bronze and traditional Turkish clothing. In the end, neither representation of the saint had any hold on the religious affections of the locals, and neither one complied with the commercial demands placed on them.